Transit-Oriented Communities

Connecticut must get on board for dense, mixed-use development with diverse housing options near rail and bus routes

What’s good about “TOCs”?

Better jobs, better tax base

TOCs grow our local and state economy by connecting businesses to customers and employees to jobs while maximizing state investments and existing infrastructure

More homes, more diversity

TOCs with affordable housing — which we think should be a healthy percentage of larger developments — cuts costs for families and diversify communities.

Less cars, less pollution

TOC can reduce reliance on cars, cutting down on draining commutes, promoting walking, and cleaning our air — all of which benefit vulnerable and low-income people.

Download our one-page Fact Sheet on Transit Oriented Communities! Scroll down for train-station-specific one-pagers.

You can advocate for your community to become a transit-oriented community

Join pro-homes advocates from across the state in organizing a “TOC Walk Audit” around your local transit station to build momentum for TOCs at the local and state level. Learn everything you need to know to run a successful and fun in-person audit!

FAQs

What is your specific proposal? See our Work Live Ride page. But note, our proposal does NOT require lot-by-lot rezoning: towns can decide to leave some single-family zones exactly as they are.

Under Work Live Ride, a town or city that opts-in has discretion as to how it achieves the overall average of density under its TOC District designation. The P&Z can allow live-work units, mixed-use developments, a mix of single-family and multi-family housing, or simply multifamily housing. They can set architectural standards to ensure that the new housing fits right in. And municipalities with multiple stations can even decide to create a TOC District t around just one of the stations. Work Live Ride allows for a lot of flexibility within statewide benchmarks that recognize the differences in transit infrastructure and population in our communities.

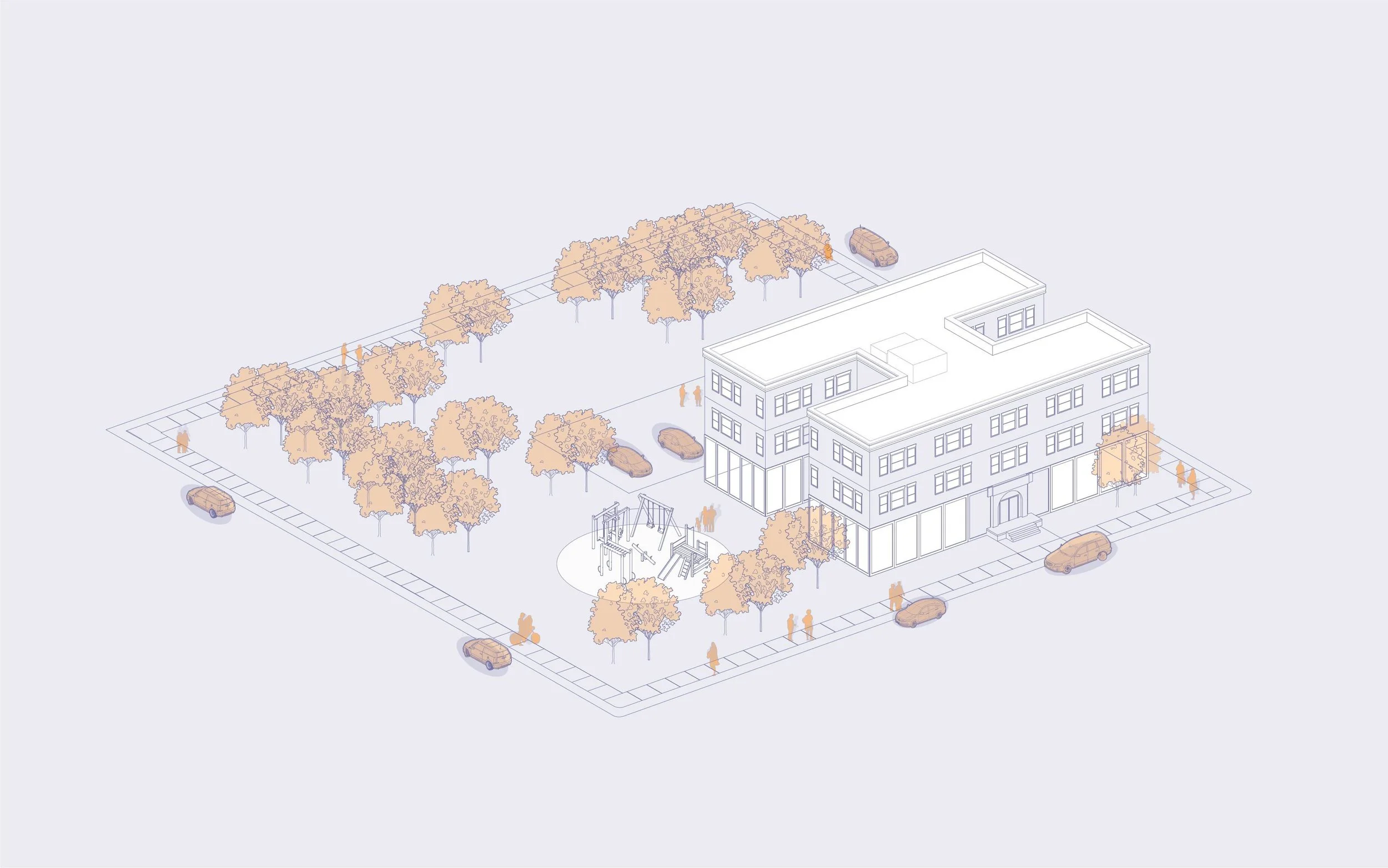

We also propose up to 20% of homes be set aside for affordable housing depending on local market conditions. We estimate less than half a percent of land in the State would be affected by our proposals, but because of the land’s location, it would have a significant positive effect. Here are two images of what 15 homes per acre for Transit Communities looks like:

How many homes would each town have to enable? It will vary by town. To calculate the total number of units required, towns would first take the number of acres within the radius of their transit station(s), and subtract out roadways, wetlands, steep slopes, lands subject to sea-level rise flooding, conservation land, parks, and state-owned land (among other things). After these common-sense exemptions, we guess the land that’s left may be about 25-30% of the land in the radius. Multiply that acreage by 15-30 units per acre depending on the category, and you have the number of units for the town must enable to be built. One estimate suggests as many as 300,000 homes could be permitted under Work Live Ride.

As noted above, the local planning and zoning body will decide what configuration the units will be. There’s lots of flexibility for towns and cities.

What is considered a “transit station”? We define a transit station as a station for commuter rail, bus rapid transit (CTfastrak), or local bus. You can find all of Connecticut’s rapid transit stations (rapid bus or rail) on our Zoning Atlas. We currently do not map local bus service on our atlas.

Does Connecticut have transit-oriented communities? Yes. Transit-oriented communities are the definition of New England Character and define some of our most beloved and successful communities and neighborhoods. We lost our love of them for much of the 20th century, but they are increasingly popular in Connecticut, with local officials and developers working in tandem to bring context-sensitive economic growth to their communities. Successful examples include new construction of Saybrook Station at the Old Saybrook Amtrak/CTrail station, 616 New Park at one of West Hartford’s two CTfastrak stations, and more recent groundbreakings in Fairfield and other towns.

What needs fixing? Our Zoning Atlas and our Issue Brief shows that there is a huge opportunity to unlock the potential of public investment in transit stations. Areas around these stations are often not zoned to satisfy local demand for housing in convenient locations.

Have any other states adopted a similar proposal? Yes. In 2021, Massachusetts adopted the Housing Choice Act, which required 175 communities with MBTA stations to rezone areas around train stations for 15 homes per acre. The Massachusetts legislation was adopted with bipartisan, near-unanimous support and signed into law by Republican governor Charlie Baker. New York’s Democratic governor Kathy Hochul has also proposed a sweeping transit-oriented zoning proposal in the 2023 session. Be sure to let Governor Lamont know that New York and Massachusetts are closing in on us if you contact him!

Would this new housing help commuters? The Connecticut Department of Transportation reports that half of all state residents travel less than 10 miles to work daily. An additional 30% of the population travel only 10-24 miles to work. That means the vast majority of Connecticut workers travel relatively short distances to get to work. Wouldn’t it be great if more of these workers could ditch their cars and hop on a bus or train, getting to work faster? Unfortunately, that’s impossible now, because we have built too much housing far away from existing transportation. The result is that 78% of all Connecticut commuters drive alone. By investing in transit oriented communities where people can live, work, and play, we can reduce the amount of driving people have to do. This would reduce the number of drivers on the road, making everyone’s commutes shorter and less expensive.

Would this new housing reduce heat island effects? Yes. Transit-oriented communities can ensure we pave less and make development more compact, therefore reducing the amount of energy and resources needed for housing and development. Study after study has shown that focusing development around public transportation and helping people reduce their use of single-occupancy cars can mitigate the heat island effect and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. This would be especially helpful in the I-95 corridor of Connecticut, which is considered a temperature hot spot.

What about local control? As noted above, our proposal would give towns and cities discretion in creating their TOC District (Our proposal does NOT affect every parcel of land.) “As of right” development just means that the local P&Z determines what they will allow at the district level instead of at the project-by-project level. This gives communities the say they want while simplifying the process for public or private developers down the road - which reduces the cost of the homes we want to see built.

RESOURCES

Our Issue Brief about zoning around Connecticut’s rapid transit stations.

Highlight: 32 of CT's 40 Rapid Transit Communities make it hard to build homes within a half-mile of their stations. Changing that could create 116,000 new homes at no cost to taxpayers.

A website entirely devoted to transit oriented communities. A good place to start!

Highlight: Transit-oriented communities can reduce a community’s dependence on driving by up to 85%.

This policy brief on why transit-oriented communities are important to racial and income equality, the environment, and local economies.

Highlight: “Residents in neighborhoods with less parking and more diversity of building types tend to drive less and ride transit more. Plus multi-family homes are usually more energy and water efficient than single family dwellings.”

A 2020 Brookings report on why a housing affordability crisis requires statewide reform focused on transit-oriented communities.

Highlight: “Several homes on expensive land reduces the cost of each home.”

A Transit-Oriented Toolkit for Connecticut on best development strategies.

Research showing that when San Diego eliminated parking mandates around transit stations in 2019, the city saw an increase in both affordable housing and housing overall.

Highlight: “[I]n 2020, one year after comprehensive parking reform was implemented, … [t]otal housing production citywide… rose, by 24 percent. More use of the density bonus program also translated into more affordable units. The program produced over 1,500 affordable homes in 2020 – six times more than in 2019. Between 2016 and 2019, the program had never produced more than 300 affordable homes in one year.”

New Urbanism Case Study finding that the most tax-beneficial development is housing in dense, walkable areas.

Highlight: “[O]n a per-acre basis, sprawling single-use developments such as big-box stores do a poor job of providing governments with needed tax revenue. Dense, mixed-use development, usually downtown or adjacent to transit, is financially much more beneficial.”

A public agency’s report on the 2021 Massachusetts Housing Choice Bill, which legalized 15 units per acre around 175 MBTA stations and is the basis of our 2022 Connecticut proposal.

Highlight: Making reasonable land development and market assumptions, the report projects the Massachusetts law will result in 344,000 homes, roughly translating to 120,000 homes in Connecticut’s 62 stations.

A look at New Rochelle’s’ transit-oriented zoning, which in its first three years jump-started 31 development projects and (with a 10% affordability component) yielded over 650 permanently affordable units.

Highlight: The zoning changes “earned unanimous, bipartisan support from the city council, priming 12 million square feet of land for potential development,” encompassing “2.4 million square-feet of prime office space, 1 million square-feet of retail, 6,370 housing units, and 1,200 hotel rooms.”

A Quebec National Institute of Public Health showing how investing in public transportation ameliorates excessive heat in commercial corridors and reduces our dependency on cars.

Highlight: “The rising temperatures of urban areas and the effects of heat islands can be mitigated by promoting public transit, discouraging car use and promoting a model of urban development.”

A 2021 Sustainability Journal study highlighting how transit oriented communities can reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Highlight: “TOD [transit-oriented communities] can help in reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and building life-cycle energy consumption by 9-25%. The overall impact of GHG can be reduced by 36%, respiratory impacts by 8.4%, and smog by 25%.”

An Environment and Urbanization study documenting the link between better planning, the urban heat island effect, and economic growth.

Highlight: “The avoidance of single-occupant vehicle commuting cannot be overstressed as a mitigation strategy for the urban heat island when considered from either a macro- or microeconomic perspective, to say nothing of the possible impacts on the global climate.”

An International Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering study showing how transit-oriented communities can mitigate the effects of heat islands.

Highlight: Reducing the impact of traffic on the heat island effect “can only be achieved through an approach to promote the use of active and public transport, while reducing the number of parking spaces, creating a pedestrian environment, and making [developing] the vegetation of the city.”

In the study, they found that traffic is a major component of the heat island effect.

More stats about the environmental benefits of transit use:

“Riding a bus instead of driving alone for a 20-mile round trip commute can save 4,800 pounds of CO2 per person annually. For every dollar spent in public transportation, $4 is generated in economic return. And for every $1 billion invested in public transportation, 36,000 jobs are created and supported.” Save the Sound

U.S. bus transit, “which has a quarter of its seats occupied on average, emits an estimated 33% lower greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile than the average single occupancy vehicle.” US DOT

Building transit-oriented communities can reduce emissions by two thirds:

Heavy rail: 0.23 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile

Commuter rail: 0.33 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile

Single occupancy car: 0.96 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile. US DOT

“American households that produce the least amount of carbon emissions are located near a bus or rail line.” Center for Climate and Energy Solutions

RAPID TRANSIT COMMUNITY ONE-PAGERS

Click on the links below to find graphics showing how your town or city currently zones around your rapid transit station!